All songs on this album were written by Dave Overland.

Category: Music

Dream a New Life (2026)

Don’t be afraid…Let your soul take flight. New mix and master.

Release of Horse Latitudes remaster – 2025

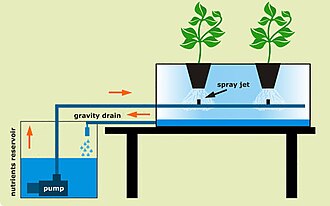

At long last, the 2025 remaster of Horse Latitudes album is available – you can listen (and purchase) it here: https://stevekeith1.bandcamp.com/album/horse-latitudes. The term Horse Latitudes is described below and is used as a metaphor in the song ‘Horse Latitudes’ (on this album) for how family life may be hectic and fast moving, but then as you age, the winds slow down and give you time to think and maybe regret the silence created.

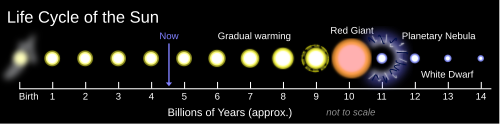

The horse latitudes are the latitudes about 30 degrees north and south of the equator.[1] They are characterized by sunny skies, calm winds, and very little precipitation. They are also known as subtropical ridges or highs. It is a high-pressure area at the divergence of trade winds and the westerlies.

Etymology

A likely and documented explanation is that the term is derived from the “dead horse” ritual of seamen (see Beating a dead horse). In this practice, the seaman paraded a straw-stuffed effigy of a horse around the deck before throwing it overboard. Seamen were paid partly in advance before a long voyage, and they frequently spent their pay all at once, resulting in a period of time without income. This period was called the “dead horse” time, and it usually lasted a month or two. The seaman’s ceremony was to celebrate having worked off the “dead horse” debt. As west-bound shipping from Europe usually reached the subtropics at about the time the “dead horse” was worked off, the latitude became associated with the ceremony.[2]

An alternative theory, of sufficient popularity to serve as an example of folk etymology, is that the term horse latitudes originates from when the Spanish transported horses by ship to their colonies in the West Indies and Americas. Ships often became becalmed in mid-ocean in this latitude, thus severely prolonging the voyage; the resulting water shortages made it impossible for the crew to keep the horses alive, and they would throw the dead or dying animals overboard.[3]

A third explanation, which simultaneously explains both the northern and southern horse latitudes and does not depend on the length of the voyage or the port of departure, is based on maritime terminology: a ship was said to be ‘horsed’ when, although there was insufficient wind for sail, the vessel could make good progress by latching on to a strong current. This was suggested by Edward Taube in his article “The Sense of ‘Horse’ in the Horse Latitudes”.[4] He argued the maritime use of ‘horsed’ described a ship that was being carried along by an ocean current or tide in the manner of a rider on horseback. The term had been in use since the end of the seventeenth century. Furthermore, The India Directory in its entry for Fernando de Noronha, an island off the coast of Brazil, mentions it had been visited frequently by ships “occasioned by the currents having horsed them to the westward”.[5]

A further explanation is that this naming first appeared in the English translation of a German book [example needed] where Rossbreiten was incorrectly understood as Pferdbreiten. The ‘Ross latitudes’ were named after the Englishman who described them first but could have been mistranslated, as Pferd and Ross are German synonyms for a horse. An incorrect translation could therefore have produced the term “horse latitudes”.[citation needed]

Formation

The heating of the earth at the thermal equator leads to large amounts of convection along the Intertropical Convergence Zone. This air mass rises and then diverges, moving away from the equator in both northerly and southerly directions. As the air moves towards the mid-latitudes on both sides of the equator, it cools and sinks. This creates a ridge of high pressure near the 30th parallel in both hemispheres. At the surface level, the sinking air diverges again with some returning to the equator, creating the Hadley cell[6] which during summer is reinforced by other climatological mechanisms such as the Rodwell–Hoskins mechanism.[7][8] Many of the world’s deserts are caused by these climatological high-pressure areas.

The subtropical ridge moves poleward during the summer, reaching its highest latitude in early autumn, before moving back during the cold season. The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) can displace the northern hemisphere subtropical ridge, with La Niña allowing for a more northerly axis for the ridge, while El Niños show flatter, more southerly ridges. The change of the ridge position during ENSO cycles changes the tracks of tropical cyclones that form around their equatorward and western peripheries. As the subtropical ridge varies in position and strength, it can enhance or depress monsoon regimes around their low-latitude periphery.

The horse latitudes are associated with the subtropical anticyclone. The belt in the Northern Hemisphere is sometimes called the “calms of Cancer” and that in the Southern Hemisphere the “calms of Capricorn“.

The consistently warm, dry, and sunny conditions of the horse latitudes are the main cause for the existence of the world’s major hot deserts, such as the Sahara Desert in Africa, the Arabian and Syrian deserts in the Middle East, the Mojave and Sonoran deserts in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, all in the Northern Hemisphere; and the Atacama Desert, the Namib Desert, the Kalahari Desert, and the Australian Desert in the Southern Hemisphere.

Migration

The subtropical ridge starts migrating poleward in late spring reaching its zenith in early autumn before retreating equatorward during the late fall, winter, and early spring. The equatorward migration of the subtropical ridge during the cold season is due to increasing north-south temperature differences between the poles and tropics.[9] The latitudinal movement of the subtropical ridge is strongly correlated with the progression of the monsoon trough or Intertropical Convergence Zone.

Most tropical cyclones form on the side of the subtropical ridge closer to the equator, then move poleward past the ridge axis before recurving into the main belt of the Westerlies.[10] When the subtropical ridge shifts due to ENSO, so will the preferred tropical cyclone tracks. Areas west of Japan and Korea tend to experience far fewer September–November tropical cyclone impacts during El Niño and neutral years, while mainland China experiences much greater landfall frequency during La Niña years. During El Niño years, the break[clarification needed] in the subtropical ridge tends to lie near 130°E, which would favor the Japanese archipelago, while in La Niña years the formation of tropical cyclones, along with the subtropical ridge position, shift west, which increases the threat to China.[11] In the Atlantic basin, the subtropical ridge position tends to lie about 5 degrees farther south during El Niño years, which leads to a more southerly recurvature for tropical cyclones during those years.

When the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation‘s mode is favorable to tropical cyclone development (1995–present), it amplifies the subtropical ridge across the central and eastern Atlantic.[12]

Role in weather formation and air quality

See also: Air pollution

Main article: Monsoon

When the subtropical ridge in the northwest Pacific is stronger than normal, it leads to a wet monsoon season for Asia.[13] The subtropical ridge position is linked to how far northward monsoon moisture and thunderstorms extend into the United States. The subtropical ridge across North America typically migrates far enough northward to begin monsoon conditions across the Desert Southwest from July to September.[14] When the subtropical ridge is farther north than normal towards the Four Corners, monsoon thunderstorms can spread northward into Arizona. When the high pressure moves south, its circulation cuts off the moisture, and the hot, dry continental airmass returns from the northwest, and therefore the atmosphere dries out across the Desert Southwest, causing a break in the monsoon regime.[15]

In summer, On the subtropical ridge’s western edge (generally on the eastern coast of continents), the high-pressure cell pushes poleward a southerly flow (northerly in the southern hemisphere) of tropical air. In the United States, the subtropical ridge Bermuda High helps create the hot, sultry summers with daily thunderstorms with buoyant airmasses typical of the Gulf of Mexico and the East Coast of the United States. This flow pattern also occurs on the eastern coasts of continents in other subtropical climates such as South China, southern Japan, central-eastern South America Pampas, southern Queensland and, KwaZulu-Natal province in South Africa.[16]

When surface winds become light, the subsidence produced directly under the subtropical ridge can lead to a buildup of particulates in urban areas under the ridge, leading to widespread haze.[17] If the low-level relative humidity rises towards 100 percent overnight, fog can form.[18]

Fall Apart Blues (2025)

From the Horse Latitudes album, remix and master. Recorded and produced at Baselines Designs studio.

Morgan Bay (Dexter’s Song) 2025 New Version

I decided to sing it myself. Darren Garrett still does backing vocals near the end.

Waking up this morning

And I’m lacing up my shoes

Gonna take the boat on

A midnight cruise

Gotta get supplies

set it up like I should

Got a feeling Angel

There’s gonna be blood

Rita’s got the baby and

She’s packing up the kids

Gonna take a breather

Down in South Madrid

Dad is riding shotgun

and going thru the code

Me, I’ve got my needle

And my eyes are on the road.

Rudy’s got a problem

He’d been taking folks apart

Now he’s got my sister

And he’s going to break her heart

He’s been incognito

He’s been doing it so well

But now he’s on my table

and I’m sending him to Hell.

Dexter Morgan is a fictional character who is the antihero protagonist of the Dexter book series by the American author Jeff Lindsay, and the television series Dexter. He is mainly portrayed by Michael C. Hall in the original series and by Patrick Gibson in Dexter: Original Sin.

In both the novels and the first television series, Dexter is a highly intelligent forensic blood spatter analyst who works for the fictional Miami-Metro Police Department. In his spare time, he is a vigilante serial killer who targets other murderers who have evaded the justice system. Dexter follows a code of ethics taught to him in childhood by his adoptive father, Harry, which he refers to as “The Code” or “The Code of Harry” and which hinges on two principles: He can only kill people after finding conclusive evidence that they are guilty of murder, and he must not get caught. Dexter refers to his homicidal urges as his “Dark Passenger“; when he can no longer ignore his need to kill, he “lets the Dark Passenger do the driving”.

Dexter’s novel appearances include Darkly Dreaming Dexter (2004), Dearly Devoted Dexter (2005), Dexter in the Dark (2007), Dexter by Design (2009), Dexter Is Delicious (2010), Double Dexter (2011), Dexter’s Final Cut (2013), and Dexter Is Dead (2015). In 2006, the first novel was adapted into the Showtime TV series Dexter and its companion web series, Dexter: Early Cuts. The first season of Dexter is largely based on Darkly Dreaming Dexter, but the following seasons deviate substantially from the book series.

For his performance as Dexter, Hall has received critical acclaim. In 2009, he was awarded a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Television Series or Drama. Paste ranked Dexter Morgan number 6 on their list of the 20 Best Characters of 2011.[1] Hall was awarded a Television Critics Association Award for Individual Achievement in Drama in 2007, and was nominated five times for the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series. He reprised his role as Dexter in the miniseries Dexter: New Blood and the series premiere of the prequel series Dexter: Original Sin, and portrays him in the 2025 sequel series Dexter: Resurrection that explores the series of events that follow New Blood.

Characterization

General biography

Dexter Morgan was born in Miami, Florida, United States, in 1971.[2] At the story’s outset, Dexter remembers very little about his life prior to being adopted by Harry and Doris Morgan. Harry only tells Dexter that his biological parents both died in a car accident, and Harry brought him home from the crime scene. Harry and Doris have a biological daughter, Debra (“Deborah” in the novels) Morgan, who becomes Dexter’s adoptive sister.

When Dexter is seven, Harry discovers that the boy has been killing neighborhood pets and realizes that Dexter is a psychopath with an innate need to kill. Consequently, Harry decides to channel the boy’s homicidal urges in a “positive” direction by teaching him to be a careful, meticulous killer of people who “deserve it”—murderers who have escaped justice. Doris died when Dexter was 16, and Harry died when Dexter was 20.[3] In the second season, Dexter’s nemesis, Sergeant James Doakes, discovers that Dexter forsook a career in medicine to pursue blood spatter analysis despite being at the top of his class in medical school. He also notes that Dexter studied advanced Jiu-Jitsu in college.[4]

Both the television show and the first novel gradually reveal Dexter’s complete back story. Dexter was born out of wedlock in 1971 to a young woman named Laura (Laura Moser on the show). In the novels, Laura was involved in the drug trade.[5] In the show, Laura was a police informant for Harry and was also his mistress. Dexter’s biological father was in the U.S. Army and served in the Vietnam War, but later became a drug-addicted criminal. Dexter also had an older brother, named Brian.[5][6] When Dexter was two years old, he witnessed his mother’s brutal murder at the hands of three drug dealers. For two days, Dexter and Brian were left in a crate, surrounded by dismembered body parts and sitting in a pool of blood.[a] Harry adopted Dexter, while Brian was left to the child welfare system.[b]

Dexter only remembers his mother’s murder later in life, when he is called to an extremely bloody crime scene left by his brother—who has also grown up to be a serial killer. In the novel, Brian escapes Miami, but returns in Dexter Is Delicious. On the show, however, Dexter catches and (reluctantly) kills Brian, aware that Brian would never stop trying to kill Debra or other innocent people.[5]

Psychological profile

Since childhood, Dexter had homicidal urges directed by an inner voice he calls “the Dark Passenger”; when that voice cannot be ignored, he “lets the Dark Passenger do the driving”. He abides by a moral code taught to him by Harry: He can only kill people who are themselves murderers; he must find conclusive proof of their guilt before killing them; and he must be careful and methodical enough to avoid getting caught.

Dexter considers himself emotionally divorced and separate from the rest of humanity; in his narration, he refers to “humans” as if he is not one himself. He makes frequent references to an internal feeling of emptiness, and says he kills to feel alive. He claims to have no feelings or conscience, and that all of his emotional responses are part of a well-rehearsed act to conceal his true nature. He has no interest in romance or sex; he considers his relationship with his girlfriend (and eventual wife) Rita Bennett to be part of his “disguise”.

Dexter likes children, finding them much more interesting than adults; accordingly, he treats victims who prey on children with particular wrath. His connection to Rita’s children, Astor and Cody, sometimes supersedes his relationship with Rita herself. For example, in the novels, Dexter continues his relationship with Rita because he realizes that Rita’s children are exhibiting the same sociopathic tendencies he did at their age, and he tries to provide them with “guidance” similar to that which Harry provided him. Early on in the show, Dexter deviates from his code of only killing murderers to kill a pedophile who is stalking Astor.

Animals dislike Dexter, which can cause problems when he stalks a victim who has pets. The novels reveal that he once owned a dog that barked and growled at him until he was forced to get rid of it and a turtle that hid from him in its shell until it died of starvation.

Dexter occasionally behaves in a way that suggests that he does feel some rudimentary human connection. He acknowledges loyalty to family, particularly to his late adoptive father, saying: “If I were capable of love, how I would have loved Harry.” Since Harry’s death, Dexter’s only family is his sister Debra, Harry and Doris’ biological daughter. Dexter admits that he cannot hurt Debra or allow anyone else to harm her because he is “fond of her”. In the first episode of season one, he says: “I don’t have feelings about anything, but if I could have feelings at all, I’d have them for Deb.”

In the first season, Dexter’s relationship with Rita sets in motion his gradual introduction to human feelings, progressing further each season. During the episode “Shrink Wrap“, when his current target is a psychologist, Dexter infiltrates his office by posing as a patient, and the doctor astutely speculates that part of Dexter’s problem in admitting to his feelings is his need for control; this revelation helps Dexter finally have real intimacy with Rita. In the second-season finale, “The British Invasion“, Dexter finally admits that he needs the people in his life.[7] In season three, when he is threatened by a target, Dexter fights to live because he wants to see his unborn child. In season four, before killing a police officer who has murdered her own husband and daughter, Dexter is overwhelmed with the realization that he does not want to lose his new family. He is also horrified when he finds out that one of his potential victims is an abusive husband and father; Dexter vehemently insists he is nothing like that and would never hurt his family.

In season five, after Rita is murdered, Dexter realizes that he genuinely loved her, and is devastated by losing her. However, after Rita’s death, Dexter became worse in many aspects. These ranged from his emotional depth to his skills as a killer, as he broke his code of not killing non-killers and innocents, once in a fit of rage,[8] and later, if it meant he remained free;[9] he was even willing to kill his ex-girlfriend, the chief of police Angela Bishop and the police sergeant Logan was Dexter’s final victim, as well as the final violation of the Code of Harry. Despite the blatant violation of the Code that was Logan’s murder, Dexter showed absolutely no remorse or guilt, instead focused solely on escaping with his son Harrison, and he even tried to justify the murder to Harrison. His last conversation with Harrison became a turning point for him—no longer could he consider himself morally superior to his victims, accepting that he himself fit the Code and that he was just another cold blooded murderer.[10]

In Dexter: Resurrection, after surviving his shooting, a physically weakened Dexter tracks his son down to protect him after Harrison starts committing his own murders. While Dexter is killing again, he has evolved and seemingly for the better, choosing to prioritize saving a killer’s next victim over killing the man, resulting in the killer escaping empty-handed. As pointed out by Dexter’s Dark Passenger, he has never done this before, meaning that Dexter has begun caring about other people for the first time. He has also reaffirmed his commitment to the Code and has gone back to basics with his kills.

Modus operandi

In both the books and the show, Dexter selects his victims according to his adoptive father’s code and kills them only after he has discovered enough evidence to prove their guilt. For each victim, he ritually prepares a kill site that has some symbolic relevance to the killer (e.g., killing a boxer in a boxing ring or a gambler in a casino’s storage shed). He completely drapes the site in clear plastic tarpaulin to catch all spilled blood, and often adorns it with evidence or photos of his victim’s crimes.

The actual capture of his victims differs between the books and the show. On the show, it usually entails approaching the victims from behind and injecting an anesthetic (specified to be an animal tranquilizer called etorphine hydrochloride, or M99 or ketamine which is the only anesthetic used in the novels, as well as a few times in the show), which renders his victims temporarily unconscious.[11] The injection is a tradition established with his first victim, the hospital nurse.[12] He uses the alias Patrick Bateman (the serial killer protagonist of Bret Easton Ellis‘ American Psycho) to procure these tranquilizers.[11] In New Blood, Dexter switches to using ketamine to sedate his victims, due to no longer being able to acquire M99 but he returns to using M99 in Resurrection. Other times, Dexter incapacitates his target by using either his hands or a garrote to cut off blood flow to the brain. In the books (and twice in the TV show), he hides in the back seat of his victim’s vehicle, then wraps a noose of fishing line around his victim’s throat when they sit down in the front seat. Dexter then uses the threat of asphyxiation to force his victim to drive them to his prepared kill site.

Once they have arrived, he either strangles them into unconsciousness or uses the noose to drag them to the kill site. In such cases, he anesthetizes them once he has informed them of his judgment. Just before the murder, Dexter collects blood trophies from his victims so he can relive the experience. Dexter’s trophy signature is slicing the victim’s right cheek with a surgical scalpel to collect a small blood sample, which he preserves on a microscope slide. Dexter did not always collect blood slide trophies though, as he initially kept a pair of his first victims earrings as a trophy, though he would dispose of them when he disposed of his second victim. Keeping trophies was something Harry condemned, as the Code was meant to separate Dexter from the people he killed.

When victims awaken, they are naked and secured to a table with plastic wrap, and for stronger victims, duct tape. If he has not already done so, he confronts them with narrative evidence of their crimes. In the novels, the method usually involves an extended “exploration” with various sharp knives; on the show, Dexter’s favored method usually involves an immediately fatal wound to the chest, neck, or gut with a variety of weapons, usually a sharp knife. He occasionally varies his methods to fit particular victims; he kills his brother (and fellow serial killer) Brian by cutting his throat with a dinner knife (with the manner of the death and Dexter’s own hesitation at inflicting the wound causing pathologists to conclude that Brian killed himself);[5] he stabs gang lord Little Chino in the chest with a machete;[13] and he kills Santos Jimenez—the man who murdered his mother—in the same manner in which his mother was killed, by dismembering him with a chainsaw. He also tries to do the same to the man who ordered his mother’s murder, Hector Estrada, but is prevented from doing so since Estrada is being used as bait against Dexter: he eventually kills Estrada simply by stabbing him in the heart. On other occasions, he uses hammers, drills, and other power tools. On a few occasions, Dexter has even resorted to killing with his bare hands, such as drowning victims or manually breaking their necks.

In the TV show, Dexter keeps his trophy blood slides from all his victims neatly organized in a wooden filing box, which he hides inside his air conditioner. In the novels, he keeps them in a rosewood box on his bookcase. Dexter, in the TV series, eventually discontinues his practice of taking blood slide trophies during the seventh season, primarily because of the potential of him being caught due to a renewed secret investigation into the Bay Harbor Butcher, and because Debra has discovered his true self and he wants to be a better person for her. In New Blood, he does take a blood slide from his first murder victim in 10 years, but does not keep it, proclaiming that he is an “evolving monster”. In Resurrection, while Dexter did not take a blood slide from his first victim in New York, he decided to go back to basics while reaffirming his commitment to the Code and took a makeshift blood slide from his next victim.

Ultimately, he dismembers the bodies into several pieces, stows them and the plastic sheeting in black opaque garbage bags, and weighs the bags down with rocks and seals them with duct tape. He then takes the bags out on his boat, the Slice of Life, and dumps them overboard into the ocean at a defined location; in the TV series, his dumping ground is a small oceanic trench just offshore. In one episode, the dump site and remains are inadvertently discovered by scuba divers, so he changes tactics, cutting the bodies into smaller pieces and dumping them further offshore, where they will be dispersed by the Gulf Stream. Original Sin reveals that for his first two kills, Dexter disposed of them in a part of the Everglades known as ‘Alligator Alley’ and did not dismember his victims, though he would be forced to resort to a different disposal site when the remains of his second victim were found. He resorted to dumping the body of his third victim in a dumpster where it would be disposed of in a landfill. By the time he disposed of his fourth victim, Dexter had settled on dumping the remains at sea, with his fourth victim being the first to be fully dismembered and disposed of in six hefty trash bags in the sea at the Biscayne Bay. In the case of his first victim in Dexter: New Blood, he still dismembers the body, but initially only buries the remains in plastic bags under a fire pit by his cabin. When an investigation begins, he burns the remains in an incinerator. The incinerator becomes his go to method for disposing of his victims, though he leaves two of his victims at the locations where he killed them because he has no time to dispose of them. In Resurrection, when he moves to New York and resumes his killing spree, Dexter continues to use an incinerator to dispose of his victims remains. The books give less detail about disposal, with Dexter usually improvising depending on the victim. He dumps some victims into the ocean, but he uses anchors to weigh the bags. He disposes of another body in a vat of hydrochloric acid.

Dexter in the book series

Darkly Dreaming Dexter

Doris Morgan, Dexter’s adoptive mother, dies of cancer when he is 16. When Dexter reaches puberty, he realizes that he is uninterested in sex and needs instruction by his father on how to behave with women. Around this time, Harry discovers that Dexter has been killing neighborhood pets and realizes that the boy has an innate need to kill. Harry decides to channel Dexter’s urges in a “positive” direction by teaching him to kill people who “deserve it”, and to get rid of any evidence so he does not get found.

When Dexter is 18, Harry is hospitalized due to a heart attack. There, Harry gives Dexter his “permission” to kill his first human victim, a nurse who is murdering her patients with overdoses of potassium nitrate.

Throughout the novel, Dexter is involved in the investigation of the “Tamiami Butcher”, a serial killer who dismembers his victims and puts the body parts in refrigerated trucks. The killer begins leaving taunting clues for Dexter to draw him in. The killer kidnaps Deborah and meets with Dexter in a storage container, and reveals their true connection: he is Brian, Dexter’s biological brother. Brian tells Dexter that as children, they witnessed their mother’s brutal murder at the hands of drug dealers, and were locked in a crate for two days, surrounded by dead bodies. Dexter persuades Brian to spare Deborah, and instead the two of them kill Lieutenant Migdia LaGuerta (this does not occur in the TV series, in which LaGuerta—whose first name is changed to “Maria”—is a recurring character until her death at the end of the seventh season).

At the end of the novel, Deborah learns of Dexter’s secret life after he saves her from Brian. She appears to accept it, but in subsequent books feels torn between her duties as a police officer and her loyalty to Dexter, whom she loves as her real brother.

Dearly Devoted Dexter

Dexter’s nemesis, Sergeant Doakes, suspects Dexter of being involved in LaGuerta’s murder, and starts following him around. Doakes and Dexter are soon forced to work together to stop “Dr. Danco”, a psychopathic surgeon who removes his victims’ limbs and sensory organs, leaving them in a state of living death.

Doakes’ pursuit forces Dexter to spend more time with Rita and her children. While attempting to bond with Astor and Cody, he realizes that they both have “Dark Passengers” of their own, and he resolves to provide them with the same “guidance” that Harry had given him. After finding FBI agent Kyle Chutsky’s ring in Dexter’s pocket, Rita believes Dexter is about to propose to her, and happily accepts before Dexter can explain.

At the climax of the book, Danco kidnaps Dexter and Doakes, mutilating the latter by removing his hands, feet, and tongue. Just as Danco is about to turn his attention to Dexter, however, Deborah bursts in and kills him, saving Dexter’s life.

Dexter in the Dark

In Dexter in the Dark, the third novel of the series, the third-person narrative reveals through an entity referred to as “IT” that the Dark Passenger is an independent agent inhabiting Dexter, rather than a deviant psychological construction. Later, Dexter realizes the Dark Passenger is related to Moloch, a Middle Eastern deity worshiped in Biblical times. The Dark Passenger is one of Moloch’s many offspring; Moloch had many children (formed through human sacrifice), and learned to share its knowledge with them. Eventually, there were too many, and Moloch killed the majority; however, some of them escaped into the world. In the novel, Dexter learns of the Dark Passenger’s true nature when it briefly “leaves” him, frightening him into researching possible reasons for its existence.

By now, Dexter had embraced his role as stepfather to both children, but is annoyed when thoughts of them—wondering if Cody had brushed his teeth before bed and if Astor had set out her Easter dress for picture day at her school—distract him from hunting an intended victim. By the end of the book, he had begun training Astor and Cody to be careful, efficient killers, with great success: when the novel’s antagonist, a Moloch-worshipping cult leader, kidnaps the three of them, Cody saves Dexter’s life by killing one of his henchmen.

The novel ends with the Dark Passenger returning to Dexter on his wedding day.

Dexter by Design

Dexter by Design opens in Paris, with Dexter and Rita on their honeymoon. There, while visiting an art gallery, Dexter and Rita see an avant-garde performance piece called “Jennifer’s Leg” in which the artist amputates her own limb. When they return to Miami, Dexter crosses paths with a suspicious homicide detective and a serial killer who preys on tourists: though the killer had initially only stolen corpses to mutilate and pose for art, he switches to actually killing people when his lover becomes one of Dexter’s victims, with Dexter’s murder of the lover being caught on a video camera that the two had hidden and used to record the mutilated corpses. Dexter also discovers that the victim was not a murderer or even an attempted murderer, and leaves him feeling some semblance of guilt due to the fact he accidentally broke the Code and killed an innocent man. In the novel’s closing paragraphs, Dexter learns that Rita is pregnant with his child.

Dexter Is Delicious

In Dexter Is Delicious, Dexter grapples with raising his infant daughter, Lily-Anne, and wonders if she can help restore his humanity. Brian reappears in Dexter’s life, situating himself with Dexter’s family. The main event for the Miami Police Department is related to the appearance of cooked, partially eaten bodies and the disappearance of a teenage girl, Samantha. Dexter has sex with Samantha while under the influence of ecstasy, and tries to prevent Rita from finding out while helping Deborah solve the murders.

The novel reintroduces Dexter’s brother, Brian, who shows up unexpectedly at Dexter’s doorstep and inserts himself into his brother’s new family. Dexter is reluctant at first to let Brian back into his life, but changes his mind when he sees him bond with Astor and Cody over their shared bloodlust.

Double Dexter

In Double Dexter, Dexter is seen by an anonymous Shadow while killing a victim in a secluded house. He continues on with his life until he starts receiving threatening emails from the person who claims to have seen him over a pile of dead body parts. Instead of turning him in, the Shadow, as he is referred to, takes it upon himself to take Dexter down. While Dexter tries to find and dispose of this Shadow, he quickly finds out that this person is much more capable than he initially suspected. Dexter is eventually framed for a murder, at least circumstantially, by his still anonymous Shadow.

While on suspension from the police force for being a ‘person of interest’ in a murder investigation, Dexter finally finds out who his Shadow is: Doug Crowley. When he goes to dispatch Crowley, he finds he is once again being tailed by Doakes. Realizing that no way exists to take down Crowley with Doakes on his tail, he enlists the help of his brother, Brian, and finally thinks that his problems have been taken care of.

While Brian is dispatching Doug Crowley, Dexter goes down to Key West with his family. Despite learning from his brother that a Doug Crowley had been taken care of, he finds the body of Detective Hood, the lead detective investigating him for murder, in his hotel suite, with the only explanation being that Brian killed the wrong Doug Crowley.

While Dexter is preoccupied with the Key West police, Crowley finally attacks Dexter by abducting Cody and Astor. Dexter hunts Crowley down to a small island off the coast of Key West. He finally gets the drop on him, and Crowley escapes with Astor on a speedboat. Dexter manages to sneak aboard and overpower Crowley, with some assistance from Astor. They shove Crowley overboard, where he is eaten by a hammerhead shark.

With Crowley dead, Dexter can finally focus on clearing his name in the murder investigation. He plants evidence in Hood’s apartment, thoroughly discrediting him, while Doakes is now under review for excessive force and intimidating a witness. These developments leave Dexter in the clear.

Dexter’s Final Cut

Deborah and Dexter are assigned as “technical advisors” to the stars of a police procedural TV series. Deborah is shadowed by female lead Jackie Forrest and Dexter is left with over-the-hill star Robert Chase. Sensing a strangeness in him, Dexter keeps Robert at arm’s length. When a series of murders leads Miami Metro’s Detective Anderson through a loop, Dexter is assigned to guard Jackie.

Deborah and Dexter quickly realize that the string of bodies all bear a striking resemblance to Jackie. Dexter is assigned to protect her in her hotel room. At first, things seem perfectly routine; Dexter accompanies Jackie to the station each morning and returns with her to the hotel at night, but when the killer’s identity is revealed to him, Dexter’s “Dark Passenger” leads him out into the streets in pursuit.

While working a crime scene where police have found another body matching the pattern of Jackie’s obsessed fan, Dexter notices a man fitting the description in a kayak out in the bay watching the scene. Stealing away to his boat, Dexter slips alongside the man and kills him. After a hard day’s work, they return to the hotel only to be disturbed in the night by sirens; Jackie’s assistant Kathy has been murdered in the room below. The murder seems to fit the pattern, but Dexter notices several errors. That night, Dexter and Jackie have sex, and start a brief but intense affair. Dexter thinks he has fallen in love with Jackie, and considers leaving Rita.

Dexter is called onto the set to appear as a minor character in the series following a conversation with Jackie and Robert. Suddenly, Dexter gets a panicked phone call from Rita: Astor has disappeared. Fearing the worst, Dexter goes in search of Robert, who had shown a suspicious interest in Astor. He questions the show’s director, who confirms that Robert is a pedophile. Moments later, he finds Jackie’s dead body in her trailer. Dexter then pieces it together: Robert killed Kathy after she caught him in a compromising position with Astor, and then killed Jackie when she found out what he had done. Dexter follows a hunch and heads to Rita and his new house. Robert catches him sneaking in and knocks him unconscious.

Waking sometime later, Dexter finds Astor and Robert together in the house. Robert has lured Astor with promises of stardom, and she appears ready to help him to kill Dexter. Thinking quickly, Dexter tells Astor that Robert will be arrested and sent to prison, and is thus useless to her. When Robert tries to take Astor as a hostage, she stabs him to death. Dexter realizes that circumstantial evidence implicates him as the murderer of Robert and Jackie, and that the only person who can exonerate him is Rita. When Dexter searches the house, however, he finds that Rita is dead, murdered by Robert. Dexter sees that his luck has finally run out, and waits for the police to arrive.

Dexter Is Dead

In Dexter Is Dead, the final book in the series, Dexter is in jail after being charged with Robert’s crimes—thanks to the corrupt Detective Anderson, who has falsified evidence and reports to make it seem that Dexter is guilty. Only Miami Metro’s head forensic scientist Vince Masuoka tries to clear Dexter’s name, but he gets swatted down by everyone from the beat cops to the state attorney. Deborah, meanwhile, has disowned Dexter for cheating on Rita and putting Astor in danger, and taken custody of his children.

Dexter’s brother Brian bails him out of prison and gets him the best lawyer in town, but the lawyer happens to be in the pocket of a powerful Mexican drug cartel led by a man named Raul, who is after Brian. The cartel tries to kill Dexter several times to get to Brian. Eventually, Dexter and Brian find out their lawyer sold them out to the cartel, so they kill him and the cartel’s members who were sent to kill them, save for one, whom they torture to find out where the cartel’s leader, Raul, is holding Cody and Astor.

Dexter and Deborah repair their relationship, and team up with Brian to save Astor and Cody. They storm Raul’s yacht and take the kids back. Deborah and the kids get away, but Brian is killed by a bomb and Raul shoots Dexter in the shoulder. Dexter kills Raul and sets a bomb so no evidence is left, then jumps off the boat into the water and sinks into the ocean. The book leaves it open to interpretation whether he survives.

Dexter in the television show

Season one

By the start of season one, Dexter is a blood spatter analyst for the Miami Metro Police Department; in his “secret life”, he is a serial killer who preys on people who are themselves murderers. In his private life, Dexter maintains superficial relationships – with his sister Debra (Jennifer Carpenter), his girlfriend Rita (Julie Benz), and Rita’s children, Astor (Christina Robinson) and Cody (Daniel Goldman in season one, Preston Bailey in subsequent seasons) to appear normal. Dexter has internal conversations with his late foster father, Harry Morgan (James Remar), who gives him advice about killing and navigating his personal life.

Rita’s previous, abusive marriage leaves her afraid to have sex, which suits the asexual Dexter perfectly. When she overcomes her demons and becomes more amorous, however, Dexter considers ending the relationship, fearing that she will see him as he really is if they become a real couple.[14] However, during a therapy session with one of his intended victims, psychologist Emmett Meridian (Tony Goldwyn), Dexter is put into a state of deep relaxation, wherein he sees a frightening image of a small boy sitting in a pool of blood. In a heightened emotional state, he runs to Rita’s house for comfort, and they have sex.[14]

Meanwhile, a serial killer of prostitutes appears in Miami, and Dexter notices that the killer is leaving hidden clues at the scene that have personal significance to Dexter. One day, Dexter receives official notification that a man named Joseph Driscoll is his biological father, and that, since Dexter is the only next of kin, he must come settle the estate and claim the body. Debra’s new boyfriend, Rudy Cooper (Christian Camargo), insists that they accompany Dexter and Rita to clean out the house. Dexter doubts that Driscoll is his father, but while cleaning, discovers a thank-you card that he sent his blood donor as a child, as Dexter has a rare blood type (AB-).[15] As Harry had convinced Driscoll to donate the blood anonymously, Dexter had no idea from where it had come.[15] Dexter suspects his father’s death was foul play, but the body is cremated before Dexter can obtain proof.[15] The show reveals to the viewer that Rudy murdered Driscoll with an injection of insulin designed to mimic a heart attack.[15]

Dexter’s rivalry with Rita’s recently paroled ex-husband Paul (Mark Pellegrino) turns violent; Paul tries to fight Dexter, who knocks him unconscious. To cover his tracks, Dexter injects Paul with heroin and leaves him to be found. Paul fails a drug test (thus breaking his probation) and returns to jail.

Dexter is called to analyze a hotel room flooded with the blood of multiple persons. The sight triggers a panic attack and calls up several memories of himself as a child sitting in blood.[16] His research leads him to discover he witnessed his mother’s murder as a child, and he had a brother named Brian. Eventually, the Ice Truck Killer (who turns out to be Rudy) kidnaps Debra after proposing to her, then drugs her and takes her to Dexter’s childhood home. When Dexter goes to rescue Debra, he finally recognizes Rudy as his long-lost brother, Brian Moser.

Brian proposes that they begin to murder together, and leads Dexter to a bound and drugged Debra, suggests that she be their first kill. After wrestling with internal conflicts from his attachment to his biological brother and need to protect his adoptive sister, Dexter ultimately decides that his loyalty lies with Debra. Later on, Brian begins to hunt down Debra himself, but Dexter apprehends Brian and then ties him down to an operating table in Brian’s apartment. Dexter tearfully slits Brian’s throat, staging the crime scene to make it look like Brian committed suicide. Eventually, the police find the body and close the case. The season ends with Dexter wondering what it would be like if everyone knew his secrets and imagining being celebrated outside the police station by an adoring crowd.[5]

Season two

In season two, Dexter is so haunted by killing his own brother that he cannot resume killing. To make matters worse, Debra, traumatized by her ordeal with the Ice Truck Killer, moves in with Dexter, which hinders his secret life. Dexter’s nemesis, Sergeant James Doakes (Erik King), harbors lingering suspicions about Dexter’s possible connection with the Ice Truck Killer, and he begins to tail Dexter everywhere. To throw him off, Dexter reluctantly refrains from killing for a month. Just as Dexter finds a chance to kill again, over 30 bodies (Dexter’s victims) are found in a Miami harbor, provoking a massive search for the so-called “Bay Harbor Butcher”.

Rita soon figures out that Dexter has been lying to her and concludes that Dexter is a heroin addict; Dexter vaguely confesses to having “an addiction” in order to hide his real secret. Rita forces him to attend Narcotics Anonymous meetings, where he meets Lila Tournay (Jaime Murray), who becomes his sponsor. Lila convinces him to explore his past, and while under extreme duress after confronting and killing his mother’s murderer, his relationship with Lila becomes sexual. Dexter confesses to Rita, who dumps him. Lila becomes obsessed with Dexter, believing he is her soulmate. Eventually, however, Dexter’s desire to be with Astor and Cody compels him to ask for Rita’s forgiveness; she grants it, and they get back together. Dexter learns that Lila is in fact a sociopath who attends NA meetings to vicariously experience emotions she is incapable of feeling, and tells her to leave him alone. Lila retaliates by framing Dexter’s colleague and friend Angel Batista (David Zayas) for rape, though he is eventually cleared.

Doakes’ suspicions subside some when he realizes that Dexter is attending Narcotics Anonymous, but he begins to suspect this is a cover for an even worse secret. As Doakes gets closer to discovering the truth, Dexter provokes him into a physical altercation at work, resulting in Doakes’ suspension. In “The British Invasion“, Doakes finally catches Dexter in the act of disposing of a dismembered body in the Florida Everglades. Dexter is forced to take Doakes captive and sets about framing him. Lila discovers the cabin in the Everglades where Dexter is holding Doakes and blows it up (with Doakes inside), to protect Dexter. The police eventually find Doakes’ charred body, surrounded by Dexter’s murderous paraphernalia, and conclude that Doakes was the Bay Harbor Butcher, much to Dexter’s relief.[7]

Dexter pretends to want to run away with Lila, but she soon discovers that he intends to kill her. Lila kidnaps Astor and Cody, and when Dexter finds them at her house, she sets it on fire and leaves the three of them locked inside. Dexter manages to save the children and escape unhurt. Weeks later, he follows Lila to Paris, where he thanks her for showing him his “true self” before killing her.[7]

Season three

In season three, Dexter finds his life manageable until he discovers that Rita is pregnant.[3] Dexter, afraid of what kind of father he would be, considers leaving Rita to parent alone, until Debra convinces him that he would be a great father. After a few failed marriage proposals, Dexter proposes again by mimicking a declaration of love from one of his victims. Rita finally accepts, with her children’s blessing.[3]

Meanwhile, after killing Oscar Prado in self-defense while attempting to murder a homicidal drug dealer named Freebo, Dexter forms an unlikely friendship with Oscar’s brother, Miguel (Jimmy Smits), a popular assistant district attorney.[3] While hunting down Freebo at night, Prado stumbles upon Dexter, bloody from murdering Freebo; Dexter claims he killed Freebo in self-defense. Prado offers Dexter Freebo’s bloody shirt as proof that he will not reveal Dexter’s secret.[17] The two men grow closer, and Dexter even makes Prado his best man. Prado gradually discerns that Dexter is a serial killer, and they begin to murder together according to Dexter’s “code”. When Prado deviates from the code to murder a rival defense attorney, it sets off a game of competing leverage and blackmail between the two men.[18] Dexter discovers the blood on the shirt is actually bovine, meaning that Prado was just using him as an excuse to kill. Angry and hurt, Dexter decides to kill Prado.[19]

Dexter then kills Prado[20] and marries Rita, with Debra as his “best man”.[21] After being tipped off by Prado, a serial killer called “the Skinner” (Jesse Borrego), who is searching for Freebo, kidnaps Dexter on Dexter’s wedding day. Facing certain death, Dexter resolves to keep fighting so he can live to see his son; he frees himself and kills the Skinner by snapping his neck and throwing his body into an arriving police car.

During the course of the season, Dexter justifies killing two people who do not fit his code: Nathan Marten (Jason Kaufman), a pedophile who is stalking Astor;[22] and his old friend Camilla Figg (Margo Martindale), who is dying of cancer and asks him to end her suffering.[23]

Season four

At outset of season four, Rita has given birth to a baby boy, Harrison. Dexter is happy to have a child of his own, but his responsibilities as a new father leave him too exhausted to kill.[24] Dexter finds it increasingly difficult to keep concealing his secret life, which leads to conflict with Rita and Astor, who has entered adolescence. At Rita’s urging, Dexter and she enter couples therapy.

While driving home after killing his first victim in months, Dexter falls asleep at the wheel and has an accident, and the resultant short-term memory loss causes him to forget where his victim’s body is.[24] He eventually retraces his steps and disposes of the body. After retired Special Agent Frank Lundy (Keith Carradine) is murdered, Dexter begins his pursuit of the so-called “Trinity Killer”, who has been committing ritualistic murders across the country for 30 years.[24] Once Dexter finds the killer, however, he is shocked to discover that “Trinity” is actually Arthur Mitchell (John Lithgow), a family man and pillar of his community.

Dexter assumes the alias Kyle Butler and begins to insinuate himself into Mitchell’s personal life in an effort to learn how Mitchell balances his family responsibilities with his secret life as a serial killer. To that end, Dexter repeatedly puts off murdering Mitchell, thwarts police efforts to apprehend him, and even saves Mitchell’s life when he attempts suicide. Upon getting to know Mitchell, however, Dexter realizes that he misjudged him; after spending Thanksgiving with the Mitchell family, Dexter learns that his would-be mentor is an abusive tyrant whose family is terrified of him. After getting into a violent altercation with Mitchell, Dexter insists that they are nothing alike and thinks he may be able to silence his Dark Passenger permanently.[25]

During his pursuit of Trinity, Dexter targets a photographer, Jonathan Farrow (Greg Ellis) who is accused of murder, targeting him after he seemingly threatens Debra. He acquires proof that indicate that Farrow killed the models he took photos of, before capturing and killing Farrow in his own photography studio, despite Farrow’s adamant protests that he did not kill anyone. The next day, Dexter learns that it was in fact Farrow’s assistant that had been killing the models, and he is left shaken by the knowledge that he has unintentionally violated his code.

When he returns home, Dexter makes arrangements for Rita and him to take a belated honeymoon. He sends Rita ahead and entraps Mitchell, who is trying to skip town. Before Dexter kills him with a hammer, Mitchell tells him that Dexter will not be able to control his violent urges for long, and that “it’s already over”—the same thing Mitchell tells his victims just before killing them.

Harry was right. I thought I could change what I am, keep my family safe. But it doesn’t matter what I do, what I choose… I’m what’s wrong. This is… fate

— Dexter Morgan, “The Getaway”, Episode 4.12

After returning home, Dexter calls Rita’s phone to find out if she and Harrison made it alright. He immediately hears Rita’s phone start to ring, indicating that she is in the house. Harrison then starts crying and Dexter is devastated to find Rita lying dead in the bathtub, with Harrison on the floor in a pool of his mother’s blood; she was Trinity’s final victim.[26]

Season five

The fifth season opens with a shocked, guilt-ridden Dexter clutching Harrison as the police respond to his call, in which Dexter says “It was me”. While he means that he killed her by letting Mitchell know his identity, the police interpret this as an admission of direct guilt. The FBI, however, soon clear Dexter, as he was with the police at Mitchell’s house at the time Rita was murdered.

Dexter spends the next day completely numb, unable to even fake any sort of emotion or grief. As Dexter plans to disconnect and restart, he finds himself confronted by Rankin (Brad Carter), a brash, foul-mouthed hillbilly. When Rankin insults Rita, Dexter kills him in a fit of rage. Harry tells Dexter that this act is the first human thing he has seen Dexter do since Rita’s death.[8]

Distraught over Rita’s death, Astor and Cody leave to go live with their grandparents. A struggling Dexter attempts to move on by hiring a nanny to look after Harrison while he goes out to find his next kill. He settles on Boyd Fowler (Shawn Hatosy), a convicted rapist whose connection to a string of missing women makes him the perfect target. Dexter kills Fowler, only to find Fowler’s latest kidnapping and rape victim, a young blonde woman named Lumen Pierce (Julia Stiles), who is still alive. After debating whether or not to kill her (and thus eliminate a potential witness), Dexter gives in to his better nature and decides to protect her. Lumen finds it hard trust Dexter, but comes to realize he means her no harm. She reveals that Fowler was not the only man who raped her. As Lumen gradually becomes integrated into Dexter’s life, she begs him to help her to go after her attackers; Dexter reluctantly agrees. They stalk a children’s dentist and the head of security for a high-profile motivational speaker named Jordan Chase (Jonny Lee Miller). It soon becomes clear that Chase was also one of Lumen’s attackers. Complicating the situation further is Detective Joey Quinn (Desmond Harrington), who believes that Dexter killed Rita and is getting too close to finding out Dexter’s dark secrets.

To keep the police occupied, Dexter puts them on Fowler’s trail. Dexter becomes personally acquainted with Chase and stumbles onto a photo that proves that all of Lumen’s attackers (who are also guilty of torturing, raping, and murdering 12 other women) have known each other since childhood.

Dexter eventually finds a vial of blood that Chase wears around his neck. After extracting a sample, he discovers that the blood belongs to Emily Birch (Angela Bettis), the rape club’s first victim. She provides Lumen and Dexter with the identity of the mysterious fourth attacker in the photo, Alex Tilden (Scott Grimes). Dexter allows Lumen to kill Tilden by stabbing him in the heart. Dexter and Lumen then become lovers, before continuing their hunt for Chase. As Lumen and Dexter plan to capture Chase, Dexter realizes cameras are in his apartment. Dexter, assuming that Quinn is watching him, waits for him to return to the surveillance van. As Dexter opens the door to capture Quinn, Stan Liddy (Peter Weller), a private investigator Quinn had hired to tail Dexter, stuns Dexter with a taser. After Liddy calls Quinn to bust Dexter, Dexter attacks Liddy and kills him in self-defense, after Liddy tries to stab him.

While Dexter disposes of Liddy’s body, Lumen gets a call from Emily. Emily appears frightened of Chase and threatens to call the police, but she is revealed to be setting a trap to allow Chase to capture them. Dexter returns to the apartment to find Lumen gone. He tracks Chase to the camp where the rape club had started. In a fit of emotion, he accidentally wrecks the stolen car he is driving, allowing Chase to take him prisoner. Chase brings Dexter to the building in which he is holding Lumen. As Chase is about to kill them, Dexter frees himself with a knife he had stashed and immobilizes Chase by stabbing him through his foot and into the floor. Dexter cuts Lumen free and knocks Chase out. When Chase wakes up, Dexter allows Lumen to kill him. While they are still in the kill room, preparing to move the body, Debra arrives on the scene, though her view of Dexter and Lumen is obstructed by a sheet of plastic. Dexter and Lumen, trapped, remain silent. Without requesting their identity, Debra warns them that she is about to call in backup and allows them to flee before the police arrive.

The next day, Lumen tells Dexter that she no longer feels the need to kill, and they cannot be together because Dexter’s homicidal urges will never leave him. She then leaves to return to the life she had before her kidnapping. The season ends with Dexter surrounded by friends and family at Harrison’s first birthday party.

Season six

About a year later, in Season six, Dexter has begun searching for a preschool for Harrison, though his atheism conflicts with the religious preschools to which he applies. He finds a greater understanding through Brother Sam (Mos Def), an ex-con and murderer whom Dexter once considered killing, who has since become a born-again Christian who counsels other ex-cons. Dexter initially sees Brother Sam’s religious conversion as a scam, but Brother Sam proves himself a truly changed man, and even helps Dexter through a crisis when Harrison undergoes an appendectomy.

Shortly afterward, Brother Sam is shot and mortally wounded in his garage. Dexter realizes that a friend of Sam’s, Nick (Germaine De Leon), is responsible, and swears revenge. On his deathbed, Sam forgives Nick and implores Dexter to do the same. Dexter considers sparing Nick when he initially appears remorseful, but that proves to be an act; after Sam refuses to press charges on his deathbed, Nick brags about what he did. An enraged Dexter drowns Nick in the surf, reawakening in him the presence of his dead brother, Brian, who begins to guide him in much the same way that Harry’s presence once had.

Brian convinces Dexter to go after Arthur Mitchell’s son Jonah (Brando Eaton), who appears to have also become a killer. Dexter finally catches Jonah with the intent of killing him, but he relents when he sees that Jonah feels guilty about failing to protect his sister, who committed suicide by slitting an artery in a bathtub, similar to how Mitchell killed his victims. When Jonah and his mother discovered Jonah’s sister, their mother blamed the children for their father’s shortcomings. This enraged Jonah, who then killed his mother. Learning this new information, Dexter rejects Brian and reaffirms the “Code of Harry”, leaving Jonah alive to forgive himself.

In the meantime, Dexter begins investigating “the Doomsday Killer”, a serial killer who models his crimes after the Book of Revelation. Dexter soon finds that the murders are being committed by two people: a fanatically religious college professor named James Gellar (Edward James Olmos) and his protégé, Travis Marshall (Colin Hanks). Dexter tracks Marshall down, but balks at killing him, believing that Marshall has a conscience and is simply being led down the wrong path. Dexter then resolves to save Marshall from himself.

After the death of Marshall’s sister, Dexter follows him to the old church and discovers Gellar’s body in a freezer, concluding that Marshall had been acting alone the whole time, with Gellar as a dissociative identity. After being forced to accept Gellar’s death, Marshall begins to target Dexter, managing to capture him and enact the lake of fire. Dexter escapes, however, and is rescued by a fishing boat carrying illegal immigrants bound for Florida. Marshall kidnaps Harrison to sacrifice him as the “lamb of God” during a solar eclipse, but Dexter rescues Harrison and takes Marshall to the old church. Debra walks into the church—seeking to find Dexter after a recent meeting with a therapist helped her realize that she is in love with her adoptive brother—only to see Dexter kill Marshall.[27]

Season seven

In the season seven opener, Dexter tells a bewildered Debra that he killed Marshall on impulse after Marshall ambushed him. Debra believes him at first, and helps him destroy the old church, with Marshall’s body inside. A few days later, however, Debra finds Dexter’s knives and collection of blood slides, and asks him point blank if he is a serial killer. Not knowing what else to say, Dexter replies that he is. Debra is horrified, but resolves to help Dexter stop killing by moving in with him and keeping a constant eye on him.[28]

After weeks under Debra’s surveillance, a stressed out Dexter kidnaps Louis Greene (Josh Cooke), a former coworker with a grudge against him, with the intent of killing him. Dexter relents at the last minute, however, and calls Debra so she can talk him out of it, reassuring her that there is good in him after all.[29]

Dexter escapes Debra’s watch long enough to dispose of Ray Speltzer (Matt Gerald), a brutal serial killer who had evaded prison on a technicality, and Debra comes to understand why Dexter kills. She makes a deal with him: she will not stop Dexter as long as he does not tell her about it or interfere with Miami-Metro investigations.[30]

Dexter sets his sights on killing Hannah McKay (Yvonne Strahovski), a serial poisoner, who as a teenager had gone on a cross-country killing spree with her boyfriend. Dexter subdues her and prepares to kill her, but stops when Hannah does not appear to fear him. They are both suddenly overcome with attraction and have sex.[31] Dexter falls in love with Hannah, who helps him realize that his “Dark Passenger” does not control his life.[32]

Dexter’s romance with Hannah complicates his relationship with Debra, however. Debra is intent on arresting Hannah for the murder of Sal Price, a crime writer for whom Debra had feelings, and Dexter has trouble reconciling his feelings for his girlfriend with his responsibility to his adoptive sister. To make matters worse, Miami-Metro Captain María LaGuerta (Lauren Velez) discovers a blood slide containing the blood of serial killer Travis Marshall at the scene of his death. Recognizing similarities to the Bay Harbor butcher’s methods, she begins an investigation to determine if the butcher is still alive and seeks to prove Doakes’ innocence. Her suspicions turn toward Dexter when she learns about his boat’s relocation during the Butcher investigation. LaGuerta reopens the Bay Harbor Butcher case, convinced that Doakes was innocent and that Dexter is hiding something. When Dexter tries to kill Hector Estrada (Nestor Serrano), the man who ordered Dexter’s mother’s murder, LaGuerta arrives at the scene, forcing him to let Estrada go so he can escape. Dexter deduces that LaGuerta had orchestrated Estrada’s release from prison to set Dexter up.[33]

At the beginning of the season, mobster Isaak Sirko (Ray Stevenson) vows to kill Dexter to avenge his lover, Viktor Baskov (Enver Gjokaj), a cop killer and one of Dexter’s victims. Fearing for his family’s safety, Dexter engineers Sirko’s arrest, but Sirko is soon released on bail and resumes his vendetta. Sirko asks for Dexter’s protection against his former associates, who fear that he will testify against them; in return, he promises Dexter that he will let him live. Dexter refuses, but ends up inadvertently coming to Sirko’s aid when one of his former henchmen attacks them both. Dexter kills the mobster, but is too late to save Sirko, who is mortally wounded during the struggle. As he dies, Sirko reassures Dexter that he can still find happiness.[34]

Debra gets into a near-fatal car accident following a confrontation with Hannah, and insists to Dexter that Hannah poisoned her. Dexter refuses to believe it at first, but he is suspicious enough to order a toxicology screen on Debra’s water bottle. To Dexter’s horror, the results prove that Hannah had spiked Debra’s water with an overdose of Xanax. Left with no other choice, Dexter gives Debra proof that Hannah murdered Price and looks on, heartbroken, as Debra arrests her.[33]

LaGuerta has Dexter arrested for the Bay Harbor Butcher murders, but Dexter is released thanks to evidence he had tampered with to throw her off his trail. Dexter is certain that LaGuerta will not give up, however, and resolves to kill her, even though doing so would be a violation of his “code”. He kidnaps and kills Estrada to lure LaGuerta in, and then knocks her unconscious, planning to shoot her to make it look like Estrada killed her. At that moment, Debra bursts in, holding Dexter at gunpoint and begging him not to go through with it. LaGuerta regains consciousness and urges Debra to kill Dexter. Seeing no way out, Dexter resigns himself to his fate and tells Debra to “do what you have to do”. Much to Dexter’s surprise, however, Debra turns the gun on LaGuerta, and shoots her dead. As the countdown to the new year begins, Dexter wonders if this is the “beginning of the end”.[35]

Season eight

The eighth season opens six months later, with Dexter growing increasingly worried about Debra, who has quit the police force and spiraled into depression and self-destructive behavior. Dexter goes to her new job as a private investigator and learns that Debra is pursuing, and sleeping with, drug dealer Andrew Briggs (Rhys Coiro). When Dexter confronts her, Debra tells him that she wishes she had killed him instead of LaGuerta. A few days later, Dexter learns that an assassin, El Sapo (Nick Gomez), is going to kill Briggs and Debra, and Dexter goes to Debra’s hotel to save her. A scuffle ensues, in which Dexter kills Briggs. He begs Debra to come with him, but she refuses.[36] Soon afterward, El Sapo is found dead, and Dexter is called in to investigate. He discovers that some of the blood at the scene belongs to Debra. She admits to killing El Sapo, and Dexter reluctantly covers up the crime.[37]

Dexter meets Dr. Evelyn Vogel (Charlotte Rampling), a neuropsychiatrist consulting with Miami Metro about a serial killer dubbed “the Brain Surgeon” who removes parts of his victims’ brains. Vogel, a specialist in the neuropathology of psychopaths, tells Dexter that she knew Harry, and helped him to invent Dexter’s “code” because she believes that psychopaths can play useful roles in society. Vogel says the “Brain Surgeon” is one of her former patients, and asks Dexter to kill him before he goes after her.[36]

Quinn calls Dexter to tell him that Debra has shown up at Miami Metro, blind drunk, and confessed to killing LaGuerta. Panicked, Dexter rushes over with Vogel in tow, and knocks Debra unconscious with a low dose of the tranquilizer he uses on his victims. He realizes he cannot help Debra and asks Vogel to treat her.[38]

Dexter starts looking into another of Vogel’s former patients, serial killer A.J. Yates (Aaron McCusker). He saves one of Yates’ victims and confronts the killer, who escapes. The following day, Debra asks Dexter to take a drive with her so they can talk. During the drive, she intentionally crashes the car into the bay, intent on killing them both. Debra survives, however, and saves Dexter’s life.[39] When Yates kidnaps Vogel, the two of them put aside their differences to track him down. Dexter kills Yates to keep him from harming Debra, and he and Debra reconcile.[40]

Dexter sets his sights on a new victim: Zach Hamilton (Sam Underwood), a teenager from a wealthy family who murdered his father’s mistress and is now preparing to kill his father. Dexter kidnaps Zach, who admits that he enjoys killing and will do it again. Seeing in Zach a kindred spirit, Dexter promises to teach him how to kill without getting caught.[41] When Dexter’s neighbor Cassie Jollenston (Bethany Joy Lenz) is murdered, he at first believes Zach is responsible and decides to kill him. Dexter confronts Zach, who swears that he did not target Cassie, but another murderer, giving Dexter hope that Zach can be “trained” after all. That hope is dashed, however, when Dexter finds Zach’s dead body in his apartment — with a piece of his brain missing.[42]

Hannah reappears in Dexter’s life when she non-lethally poisons him and Debra to get his attention.[41] Dexter investigates and finds that she has changed her name and married Miles Castner (Julian Sands), a wealthy businessman. Dexter goes to see Hannah, who says she had wanted him to kill Castner, but changed her mind after realizing she is still in love with Dexter. Dexter goes to Castner’s boat to protect him, but finds that Hannah has already killed him. The two of them dispose of the body, and Dexter arranges for her to leave the country.[43] The night before Hannah leaves, however, Dexter and she have sex, and he realizes that he is still in love with her. They renew their relationship, and plan to run away together to Argentina.[44]

After investigating, Dexter discovers that Zach’s killer is Vogel’s blood relative. Vogel tells Dexter that she had a son, Daniel, who as a teenager murdered his younger brother Richard before apparently dying in a fire. Dexter discovers that Daniel set the fire himself to fake his own death, and that he is now living under the identity of Oliver Saxon (Darri Ingolfsson)—Cassie’s boyfriend at the time of her murder. Dexter suspects that Saxon is the “Brain Surgeon” and warns Vogel, who tells him to stay out of it; Dexter is unaware that she is sheltering her son.[44] Dexter makes preparations to move while hunting Saxon, the last “loose end”. He goes to Vogel’s house to make sure she is safe — only to see Saxon slit her throat.[45]

Days later, Saxon shows up at Dexter’s apartment and offers a truce: he will spare Dexter’s family if Dexter will leave him alone. Dexter pretends to accept, but is now more determined than ever to kill him. He finds proof of Saxon’s murders, which he turns over to the police so that Saxon will be forced to come after him before he leaves Miami. Dexter then enlists Debra’s help in subduing Saxon and prepares to kill him. At the last moment, however, Dexter realizes that his love for Hannah is stronger than his need to kill, and he spares Saxon’s life. He calls Debra so she can arrest Saxon, and says his goodbyes to her and Harry. After he leaves, however, Saxon escapes his bindings and shoots Debra in the stomach.[46]

In the series finale, “Remember the Monsters?“, Dexter’s flight to Argentina is delayed by a hurricane, and he tells Hannah and Harrison to go on without him, intending to take care of Saxon. When he learns what has happened to Debra, Dexter rushes to her side at the hospital, but she tells him to go on and live a good life. Moments later, however, she suffers a major stroke that leaves her in a persistent vegetative state. Dexter blames himself, and realizes he will always destroy those he loves; he sees at last he can never have a happy life.[47]

After Saxon is arrested, Dexter kills him in his cell, and apparently convinces Quinn and Batista that he acted in self-defense (it is implied that they knew what really happened). Dexter goes to see Debra one last time, tearfully turns off her life support, and buries her at sea. He then fakes his own death by wrecking his boat. The series’ final scene reveals that he has assumed a new identity in Oregon as a lumberjack and begun a new life, alone.[47]

Dexter: New Blood

Approximately 10 years after the original series’ finale, Dexter has moved to the fictional small town of Iron Lake, New York, posing as Jim Lindsay, a local shopkeeper. He is in a relationship with Angela Bishop (Julia Jones), the town’s chief of police, and has abstained from killing for almost a decade. Debra has replaced Harry in Dexter’s mind as his “Dark Passenger”, albeit one who advises him on ways not to kill. He “falls off the wagon”, however, when he impulsively murders Matt Caldwell (Steve M. Roberts), an arrogant stockbroker who once killed five people and got away with it thanks to his family’s wealth and political clout.[48]

Caldwell is officially considered a missing person, and his father Kurt (Clancy Brown) begins nosing around the investigation. Dexter destroys the corpse and alters the crime scene to make it look like Matt left town after being injured. That night, he runs into Kurt, who drunkenly claims to have gotten a FaceTime message from his son. Unbeknownst to Dexter, Kurt is a serial killer who preys on runaway teenage girls, and is trying to get the search called off so the police will not find his victims’ bodies.[49]

At the same time, a now teenage Harrison (Jack Alcott) comes back into Dexter’s life, having tracked him to Iron Lake. He says he lived in a series of foster homes after Hannah died of pancreatic cancer.[48] Over Debra’s objections, Dexter once again becomes a father to the boy, who quickly becomes a popular student and star of his school’s wrestling team, and befriends Angela’s adopted daughter, Audrey (Johnny Sequoyah).[50] Harrison also causes Dexter to depart somewhat from his “code”; when Harrison nearly dies of a fentanyl overdose at a party, Dexter murders the drug dealer who sold him the pills by forcing him to ingest a lethal amount of the drug instead of his usual killing method, a stab wound to the chest.[51]

Harrison is injured in a knife fight with another student, Ethan Williams (Christian Dell’Edera), whom he badly wounds. Harrison claims that Ethan told him he was planning a school shooting and stabbed him, and that he stabbed Ethan back in self-defense. When it is discovered that Ethan was indeed planning to kill several of his classmates, Harrison is hailed as a hero, but Dexter doubts his story. Using his training as a blood spatter analyst, Dexter reconstructs the fight and determines that Harrison stabbed Ethan unprovoked, and then inflicted a superficial stab wound upon himself to make it look like Ethan attacked him. Dexter searches Harrison’s room and finds a bloody straight razor—the same kind of blade that Arthur Mitchell used to kill Rita—and realizes that his son has inherited his homicidal tendencies.[52]

During a chance meeting with Angel Batista (now Captain of Miami Metro) at a police conference in New York City, Angela learns about Dexter Morgan’s supposed death, and after some investigation discovers the true identity of “Jim Lindsay”.[51] Dexter tells her the truth about faking his death—while leaving out that he is a serial killer—but she breaks up with him regardless. This causes awkwardness between them after she catches Harrison in bed with Audrey.[53]

Meanwhile, true crime podcaster Molly Park (Jamie Chung) arrives in town to do a story about Matt Caldwell, and Dexter discovers that she did a series on the Bay Harbor Butcher. He becomes obsessed with finding out what she knows, especially after Harrison reveals that he learned the truth about Rita’s death from her show. He spies on her talking to Kurt, who lies that his son is hiding out at the family cabin, in order to lure her out there and kill her. Dexter reluctantly saves her and gets a closer look at what he correctly suspects to be Kurt’s killing ground.[53] Dexter grows alarmed as Kurt becomes a mentor to Harrison, especially after he encourages the boy to break another student’s arm during a wrestling match.[53]

When Angela finds the mummified corpse of her friend Iris, who disappeared 25 years earlier, she asks Dexter to analyze the remains, and tells him that she suspects Kurt of killing her. Dexter leads her toward investigating Kurt as a serial killer in hopes that exposing his crimes will destroy his influence over Harrison. She arrests Kurt for Iris’ murder, but Kurt surprises her by saying that his late father, Roger, committed the crime. (A flashback reveals that Kurt did indeed kill her, however.) When Kurt is released, he tries to intimidate Dexter by hinting that he knows he killed Matt, and Dexter realizes that he will have to kill Kurt to protect Harrison and himself.[54]

Kurt pays one of his truckers, Elric Kane (Shuler Hensley), to kidnap Dexter so he can kill him and Harrison, but Dexter manages to evade and kill him. Dexter arrives at Kurt’s cabin just in time to save Harrison from Kurt, who runs off. He tells Harrison that they have the same “Dark Passenger”, and for the first time truly bonds with his son.[55] At first, Dexter tells Harrison that he merely “confronts” murderers to make them stop killing, but Harrison eventually figures out that Dexter kills his victims. Harrison reveals that he remembers seeing Mitchell kill Rita, and that he has been consumed with a violent rage ever since. He then says that Kurt deserves to die, and father and son set out to kill him.[56]

Together, they find Kurt’s victims, including Park, perfectly preserved and displayed in a bunker underneath his house. Dexter intentionally triggers an alarm to let Kurt know they found his hiding place. As intended, Kurt rushes back to his house, where Dexter incapacitates him and prepares a kill site in Kurt’s own bunker. When Kurt claims that he “saved” his victims from lives of pain and suffering, Dexter kills him as Harrison watches, and resolves to teach him “the Code of Harry”. They return to Dexter’s cabin to find that Kurt had burned it down the night before. They stay with Angela and Audrey, now Harrison’s girlfriend, and start to bond as a family—until Angela finds evidence, left by Kurt, exposing Dexter as Matt’s murderer. She then sees a connection between that proof and new evidence uncovered by Park on the Bay Harbor Butcher case, and realizes that Dexter is the killer.[56]

In the finale episode, “Sins of the Father“, Angela arrests Dexter for Matt’s murder. At the station, Angela tells Dexter that she suspects him of being the Bay Harbor Butcher. While she interrogates him at the station, Dexter says that Kurt killed Matt and is framing him, and tells her she can find proof that Kurt murdered numerous women in the bunker. Distracted, Angela leaves the station to go to Kurt’s cabin. Dexter lures her deputy, Logan (Alano Miller), closer to his cell and then puts him in a headlock, demanding Logan release him. Logan reaches for his gun and attempts to shoot Dexter, but misses. Dexter breaks Logan’s neck, steals his keys and flees the station after having contacted Harrison using Logan’s phone.